Aims and objectives

This project is concerned with the collection and preservation of Hakku Patras found in the possession of nomadic and non-nomadic performing communities. They are documents of Rights, granted to performers 200-500 years ago, by the village elders or other institutions, to perform certain duties in an assigned area. Hakku Patras are fragile social documents and their contents are important for the study of rural social dynamics. They should be located, copied and thus preserved against the onslaught of urbanisation.

The documents are inscribed on copper plates and written on a piece of paper or paper scrolls. The content of Hakku Patras contains the name of the village, performing community, dates of sanctioning of the grants and form of the performance. But these documents are culturally more significant. They play an important role in the socio-cultural milieu of marginalised communities. These documents contain information which is mutually shared by all sub-castes and well understood and respected by all members of patron communities. In spite of many social upheavals the tradition is continued.

Preliminary research has identified some 40 Hakku Patras in many regions, with indications that there are many sources of documents in rural areas. In this pilot survey, it is planned to collect the details of their location. These documents can easily be damaged permanently, as their custodians are constantly moving and unable to protect them. The copper documents are relatively safe, but due to poor economic condition these documents are often sold away, mortgaged or melted down. These factors make the documents endangered and rare archival materials. Owners of these documents are relinquishing their traditional professions and adopting other remunerative vocations which provide them with more means of income. They are constantly migrating from their villages to urban industrial area working as labourers. The poor living conditions of these people left the Hakku Patras to the mercy of rain, fire and termites and made the survival of the precious documents most difficult.

An example is the potter community in a village. The potter has to make a variety of pots which include Ritual Pots, Festival Lamps, Ceremonial Pots, Water Pots, Stored Water Pots, Festival Pots and many other varieties. When the potter provides his work, combined with his skill and art to the villagers, they honour and pay their gratitude to the potter in return. It is beyond the minimum financial transaction. For instance a marriage ceremony within a family begins with the ceremonial pots (Ireni Kundalu) of the potter and the family head thanks him as per the family tradition. It is a practice current in villages. This process is part of the 'Right' reciprocated by potter and villages.

The Hakku Patras are unique in their nature as documents revealing the place and position of marginalised dependant castes in society. The dependant castes are nomadic and non-nomadic - they are story tellers, folk-narrators and caste priests. They narrate myths from the origin of the patron caste and also recite genealogies and they hold their place of importance as the folk bards, owning 'mirasi right'. They are considered to be important because of the services they render to the society. Dependant castes keep an oral record of caste and its evolution through their genealogies. Unfortunately, those who sing and recite about the social structures are eliminated by the society of their position and rights. Hakku Patras are the documents showing their rights. Up until now, academics did not notice the importance of these patras and their valuable share of work in society. Now, their existence is on the edge of extinction. To collect those patras that have survived becomes inevitable on the part of academics. The State Archives, State Museums or any other similar local institutions have not found or have on record any documents of this type. So scholars have not been aware of the existence of these documents. This project realises the true value of these documents and wants to preserve them.

Outcomes

All the project’s aims and objectives were achieved, in trying to understand not only the documents discovered in the survey but the nature and function of Hakku Patras.

The survey explored how the Hakku Patras are treated, both within the family and outside the community of the holders of this documents. The addresses of the holders of Hakku Patras have been listed and details authenticated. Some of the copper plates have been digitised following the EAP Guidelines.

During this pilot project some important information was gathered relating to these documents, including the following:

- Kakipadagalu, for nomadic performers, have a bronze crow icon with a snake on its back. It is a totemic icon of this community, which allows them a Right (Hakku) to perform in the entire state of Andhra Pradesh. There are only three such icons in existence and two have now been photographed. This is the first time in the cultural history of Andhra Pradesh, that a bronze crow icon of Kakipadagalu has been discovered.

- Gurramvaru, a sub-caste of the Mala Community, is given a Gurram (bronze horse) as a totemic icon. This bronze icon is a rare work of art and there is only one family in the entire state which possesses such an icon. It appears that these bronze horse icons have been melted down for its bronze. This horse icon from Karimnagar District has been digitised.

- Many Patams (painted cloth scrolls) have been documented - they are used by the folk performers as visual aids in their performance. These patams belong to Gudaram, Terachiralu, Kommulavaru and Addamvaru (all performing communities).

- Sawdust toys of Mandahetchulu have also been digitised. These toys are theatrical visual devices, which also provide the folk performers communities rights for their performance. All the Mandahetchulu performer communities have copper plates and fifty six sawdust toys. The fifty six toys represent various characters from the narrative of the hero Katamaraju, his family, his supporters, his enemies and Gangamma Goddess. No folk performer goes on performing tour without the copper plate and toys.

- The largest copper plates found were 12x52 cms – one belongs to the Madiga Jangalu of Kolanupaka, Nalgonda District and another at Vemulawada in Karimnagar District.

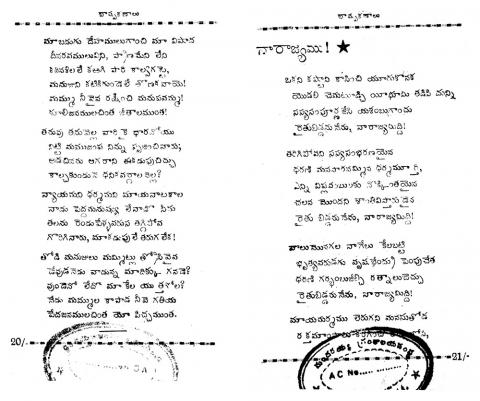

The paper documents are also important and some have been digitised. The information gathered during this pilot project will enable a future major preservation project to be carried out.

The records copied by this project have been catalogued as:

-

EAP201/1 Collection of Hakku Patras

Due to the cyber-attack on the British Library in October 2023, the archives and manuscripts database is currently inaccessible and we are unable to provide links to the catalogue records for this project.