![EAP143/1/1/80: gong zhang ze ji shu [1883]](/sites/default/files/styles/publicity_image/public/EAP143_1_1_80-LBS_0133_008_L.jpg?itok=Ac3wdRqs)

Aims and objectives

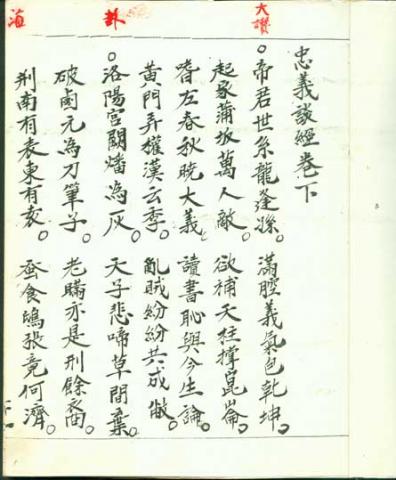

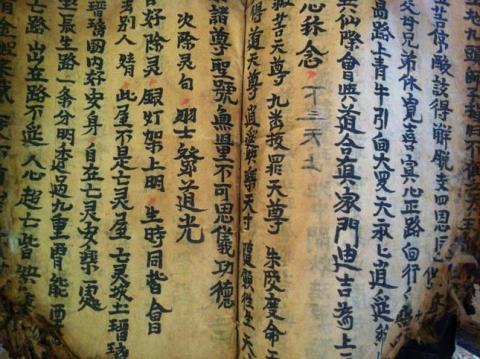

Shui manuscripts are the written records of the Shui people, an ethnic group with a population of four hundred thousand in south and southeast Guizhou, China. The writing system in Shui manuscripts, similar to that in the Dongba sutra in Yunnan, is identified as one of the few surviving hieroglyphics in China. Due to neglect in history, natural death of the last generation of scribes and the desertion of the Shui language by native people, the Shui manuscripts face the fate of extinction unless effective preservation means is in action.

As the documents accumulated over last four centuries, Shui manuscripts are not only the key materials to understand the unique culture of the Shui people but also constructive for studying history, anthropology, folklore and even palaeography in general. Similar to many aboriginal texts in various ethnic groups, Shui manuscripts are written, kept and taught by the native priesthood. The manuscripts are used in rituals, as well as in teaching the next generation of priests. The contents of the Shui manuscripts are so abundant covering aboriginal knowledge on astronomy, geography, folklore, religion, ethic, philosophy, art and history that the manuscripts are called the encyclopaedia of Shui people. The manuscripts are precious and irreplaceable for understanding the Shui people and Southwest China.

Presently, Shui manuscripts are mainly found in Sandu, Libo, Rongjiang and Kaili in Guizhou and Hechi in Guangxi. Up until ten years ago, all the Shui manuscripts had been kept in private hands. Archives in several counties have collected up to 6,000 volumes of the Shui manuscripts, but the majority of Shui manuscripts are still preserved in private collections of Sandu and Libo counties. A survey reveals that a total of around 20,000 volumes of the Shui manuscripts survive in the world. The storage condition for both the public and the private collections raises further concerns on preservation.

Many factors have made the Shui manuscripts endangered. In the aspect of the physical properties of the manuscripts, they are written (in only one case, it is printed and it is dated to 16 th century) on cotton paper, which is apt to perish if demands on space, temperature and humidity are not met. This high specification archival space is not available for state-owned county archives, let alone private. In the aspect of the social context, the manuscripts are endangered by neglect, lack of financial support, political discrimination and recent social change. Although some scholars have solicited to establish an archives or museum to preserve the Shui cultural heritages for years, very limited advance has been achieved. In the revolutionary era, the Shui priests were fiercely criticized for political or ideological incorrectness. The manuscripts therefore were viewed as meaningless, useless, and harmful by the authorities. A great many Shui manuscripts were thus discarded or destroyed in the past decades. The economic and social reform since the 1980s has brought many fundamental changes to the Shui society, as well as to the Shui manuscripts. In particular, the native Shui language has been marginalised and the priests no longer carry out the educational practice. More and more Shui people adopt Chinese in daily life and even in ritual practice. The old Shui priests find it even harder to recruit young apprentices, who have left villages to pursue their lives in cities.

Considering the abundance of the materials and the little work that has been done to date, this project will concentrate on Libo county. About 400 volumes in the county archives and 200 volumes in private collections are planned to be preserved in this project. In addition, materials at the periphery of the Shui manuscripts, which had previously been neglected, will also be included. Two major types of materials will be collected in the latter sections: the first, oral-historical interviews with senior Shui priests, since they are the last generation who knows how to write and read the Shui writings and use them in ritual practice; the second, photographs and video-recordings of Shui native rituals in which Shui manuscripts are applied. The funding of these audio and audio-visual recordings will be from alternative sources.

The project will establish a multimedia and interdisciplinary database when it is accomplished. The database will include digital images of Shui manuscripts, original Shui manuscripts, oral historical interview recordings, audio and video recordings of ritual practices, and relevant photographs.

Outcomes

During the project, the team undertook several sessions of investigation in about twenty villages in Libo county, verified the current situation of collections of Shui manuscripts in the county archives and private collections, discovered more private collections, digitised selected Shui manuscripts and undertook preliminary research on the Shui manuscript and its role in the endangered Shui indigenous culture. Approximately 600 volumes of Shui manuscripts were digitised.

The Shui manuscripts, both in the public and private collections, remain in their original locations. The digital database of Shui manuscripts is kept at the University Library of Sun Yat-sen University and the list will be available at websites of the University Library and the Institute of Historical Anthropology. Copies of the material have been deposited with the British Library.

The records copied by this project have been catalogued as:

- EAP143/1 Shui Manuscript Collection at the Libo Archives, Guizhou, China [16th - 20th Century]

- EAP143/2 Pan Yushan Collection of Shui Manuscripts [estimated 19th to 20th century]

- EAP143/3 Yang Family Collection of Shui Manuscripts at Bailai, Rongjiang [19th century]

- EAP143/4 Shui Manuscripts Digitised by Sun Yat-sen University [19th to 20th century]

- EAP143/5 Pan Changmao Collection of Shui Manuscripts [20th century]

- EAP143/6 Pan Changmeng Collection of Shui Manuscripts [20th century]

- EAP143/7 Yao Changli Collection of Shui Manuscripts [20th century]

- EAP143/8 Wei Degao Collection of Shui Manuscripts [1930s]

- EAP143/9 Shi Wenhan Collection of Shui Manuscripts [20th century]

- EAP143/10 Yang Tongbin Collection of Shui Manuscripts [1930s]

- EAP143/11 Yang Tongneng Collection of Shui Manuscripts [1940s]

- EAP143/12 Lu Tingzhang Collection of Shui Manuscripts

- EAP143/13 Wu Xingben Collection of Shui Manuscripts

- EAP143/14 Wei Tiangao Collection of Shui Manuscripts

- EAP143/15 Wei Yongji Collection of Shui Manuscripts

- EAP143/16 Wei Tianlu Collection of Shui Manuscripts

Due to the cyber-attack on the British Library in October 2023, the archives and manuscripts database is currently inaccessible and we are unable to provide links to the catalogue records for this project.